People who are slim, don’t smoke, and don’t have diabetes usually don’t worry too much about their hearts. Those with good control of their blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose levels, even less so. But an alarming new study in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology may soon change that calculus.

Researchers from Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares Carlos III in Madrid, Spain, set out to determine why people with no cardiovascular risk factors nevertheless have heart attacks and strokes. They conducted cardiac ultrasound exams and CT scans on a group of more than 1700 people ages 40 to 54 without conventional risk factors, such as high blood pressure and cholesterol levels. They also took a separate look at a subgroup of people with risk factors at levels considered optimal for good heart health—blood pressure less than 120/80 mmHg, total cholesterol less than 200 mg/dL, and fasting glucose less than 100 mg/dL.

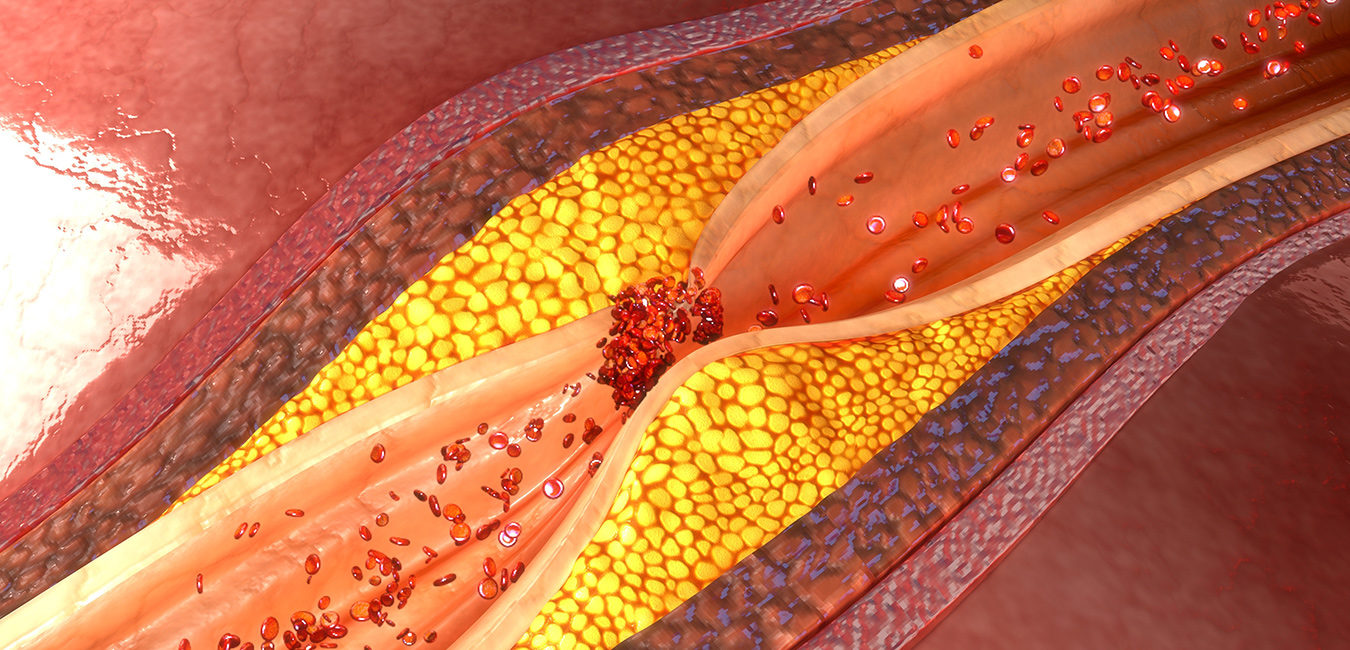

The results were striking. Almost half of these seemingly healthy individuals—those used to getting high-fives at their annual check-up with blood work—had atherosclerotic plaques, which can reduce or block blood flow to the heart. And, even among the subgroup with optimized risk factors, 38% had evidence of atherosclerosis. In other words, heart disease was already present. This hidden, undiagnosed, subclinical disease puts them at extremely high risk for a heart attack or stroke.

Atherosclerosis can develop over a period of years without any telltale signs. Although the risk of heart attacks and strokes is low among people without conventional risk factors, any build-up of plaque in the arteries can result in a cardiovascular event.

The study implicated LDL cholesterol as a major culprit for early atherosclerosis. LDL was associated with the presence of arterial plaque and the extent of disease both in people free of cardiovascular risk factors and those with optimal risk factors—even when LDL levels fell within the normal range.

“As LDL-C levels increased, there was a linear and significant increase in the prevalence of atherosclerosis, ranging from 11% in the 60 to 70 mg/ dL category to 64% in the 150 to 160 mg/dL subgroup,” the study authors reported. Current guidelines describe LDL above 160 mg/dL as “high” and those from 130 mg/dl to 159 mg/dL as “borderline high.”

Fortunately, LDL cholesterol is a modifiable risk factor. Evidence suggests a diet low in saturated fat, present in red meat and dairy products, and trans fats, which are found in fried foods and many commercial sweets and snacks, can help lower LDL cholesterol. Foods with omega-three fatty acids—primarily oily fish like salmon and mackerel—and those with soluble fiber are also recommended.

Limiting alcohol intake and moderate physical activity each have been shown to improve cholesterol. People who smoke should make every effort to stop, while those who carry around extra pounds should aim to lose the weight.

This important new data strengthens the rationale for inflammation testing in individuals who appear to be in good cardiovascular health. The Cleveland HeartLab offers an array of evidence-based blood and urine tests that shed light on an individual’s risk for future cardiac problems. For example, ADMA and even slight elevations in the microalbumin/creatinine ratio may indicate the possible presence of hidden disease. Relatatedly, MPO and Lp-PLA2, very vascular-specific enzymes, may suggest that an active disease process is underway. See www.knowyourrisk.com. Getting the right inflammation tests—and acting on abnormal results—could mean the difference between leading a rich and active life and one marred forever by an avoidable cardiovascular event.